Greek Roman Dogs Line Drawings Kids Easy

Dogs in ancient Greece are regularly depicted in art, on ceramics, in literature, and other written works as loyal companions, guardians, hunters, and even as great intuitive thinkers; all of these expressing the deep admiration the Greeks had for their dogs. The Greek appreciation for the dog, in fact, illustrates the Greek love for life and cultural value of loyalty.

Dogs were most likely first domesticated in Greece out of necessity for protection from wolves, but the relationship developed in time to one of mutual respect and love. It is possible that the early Greek appreciation for the dog was influenced by long-standing trade with Egypt, a civilization famous for their love of animals, but could have as easily developed independently.

Dog-headed Rhyton

The Trustees of the British Museum (CC BY-NC-SA)

The most basic dog collar no doubt developed on its own in Greece, but the later ones were most likely influenced by the Egyptians. The Pharaoh Amasis II (r. 570-526 BCE) founded the city of Naucratis c. 570 BCE which grew into an important trade center between Greece and Egypt. From Naucratis trade goods traveled back and forth between the two countries along with cultural diffusion of ideas, technology, religious belief, and, most likely, the concept of the dog collar beyond a simple band of leather or rope.

The scholar George G. M. James, in fact, claims in his work Stolen Legacy: The Egyptian Origins of Western Philosophy, that the Pre-Socratic Greek philosophy derived beliefs and practices from Egypt. In this same way, it is probable that the dog collar also made its way from Naucratis to Athens and the other city-states of Greece via trade. However the Greeks came to appreciate their canine friends, though, and however the collar developed, dogs became an integral aspect of ancient Greek life and were celebrated in Greek art, poetry, and honored as friends and family through images on tombs. Although the majority of Greek written works on dogs deal with hunting, many of the most famous praise them for their intelligence, resourcefulness, and loyalty.

Famous Dogs of Ancient Greece

Dogs are attested to in Greece from the Neolithic Age but the first mention of them in Greek literature comes from the work of Homer c. 800 BCE in which he describes dog sacrifices in the Iliad following the death of Patroclus (Book 23, lines 198-199) and, in the Odyssey, writes of the most famous dog in all of Greek literature: Argos, Odysseus' faithful companion (Book 17, lines 290-327). The dogs Achilles sacrifices for Patroclus are two that Patroclus raised and fed at the table and are sent with him on his funeral pyre to continue as his companions in the underworld.

Argos has waited for the 20 years Odysseus has been gone for his master's return, but when Odysseus comes back to Ithaca he is in disguise and cannot reveal himself to anyone. Argos recognizes his master and rises to greet him but Odysseus, barely holding back his tears, must turn from his old friend in order to maintain his cover, and the dog lays down and dies. Both episodes famously illustrate the loyalty of the dog and the love their masters had for them.

The most famous Greek-Macedonian dog in history is Peritas, who belonged to Alexander the Great.

The most famous Greek-Macedonian dog in history is Peritas, who belonged to Alexander the Great. Many stories have been told of Peritas gallantly saving Alexander's life in battle and the great conqueror naming a city after him, but these stories are challenged by the ancient sources which depict events in the life of Alexander's dogs and, unfortunately, they are not nearly so dramatic or noble.

According to the historian Pliny the Elder (l. 23-79 CE), Alexander was looking for a dog to fight wild boar and similar animals in contests and was given a suitable one by a king of Asia. When the dog was released into the pit, however, he just lay down and so Alexander had it killed as defective. The Asian king, hearing of this, sent word along with another dog that this particular breed was not interested in so tame a challenge as that of a boar and would only rise to fight lions and elephants. Alexander matched this new dog against these larger animals, and it did well. Upon realizing his mistake, Alexander was deeply upset over killing the first dog and named a city in his honor (Natural History, VIII, 149-150).

This version of the story of Alexander's dog has never become as popular as the one derived from Plutarch's Life of Alexander (the only ancient writer to mention the dog's name). Plutarch (l. 45-120 CE), also, never mentions the dog saving his master in battle but, in relating Alexander's grief over the loss of his horse Bucephalus, writes:

It is said, too, that when he lost a dog also, named Peritas, which had been reared by him and was loved by him, he founded a city and gave it the dog's name. (61.3.210)

The story of Peritas rescuing Alexander from the Mallians or taking down the elephant of the Persian forces at the Battle of Gaugamela seems to be an embellishment of later writers. Even the Roman writer Arrian (l. c. 89 - c. 160 CE), who includes every detail he could find on the life of Alexander and his campaigns in his work, makes no mention of the heroic dog even though he was especially fond of the animals and wrote extensively on them.

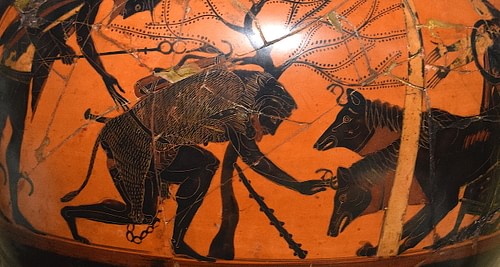

Dogs are frequently featured in Greek mythology and among the best-known is Cerberus, the three-headed dog who guards the gates of Hades. Cerberus features in a number of tales but most notably among the Twelve Labors of Heracles (the Roman Hercules) when the hero must subdue the beast as part of his trials. The goddess of the hunt, Artemis, was associated with seven hunting dogs and, as in Egypt, dogs were sacrificed to her.

Hercules Captures Cerberus

James Blake Wiener (CC BY-NC-SA)

The mysterious and ominous goddess of witchcraft, magic, and darkness, Hecate, was closely linked to dogs. Hecate was a three-headed, multi-form deity sometimes depicted with the heads of a horse, a dog, and a lion. Humans could never hear her coming, but dogs could and would bark at her approach; a dog who seemed to be looking and barking at nothing was thought to be warning of Hecate or her ghostly associates. Atalanta, the huntress who could hold her own against any man, was also associated with dogs as they were an integral part of the hunt and symbolized strength, cunning, and endurance.

Dogs as Hunters & Philosophers

Dogs as hunters, and engaged in the hunt, are among the most frequent depictions and inscriptions from ancient Greece. Dogs were not employed in Greek warfare but were used primarily for companionship, as guard dogs, and in hunting. Their value as companions and family members was emphasized in the work of the poetess Anyte of Tegea (l. 3rd century BCE) who was best known for her epitaphs for animals and, most notably, dogs. In her time, Anyte was compared to Homer for the beauty of her verse and was paid handsomely for her work.

The Greek philosopher Plato (l. 428-348 BCE, the best-known student of Socrates) famously claimed in Republic, Book II, 376b that the dog is a true philosopher. Plato's main character in Republic (as in most of his work) is Socrates who here claims that dogs are imbued with natural wisdom because they can distinguish friend from enemy based upon a "criterion of knowing and not knowing" and so must be lovers of truth and have knowledge superior to that of people. While a human may be deceived as to their true friends, Socrates argues, a dog never is. The dog cannot be fooled by appearances but sees to the heart of people and the truth of events and this is what makes the dog a true philosopher.

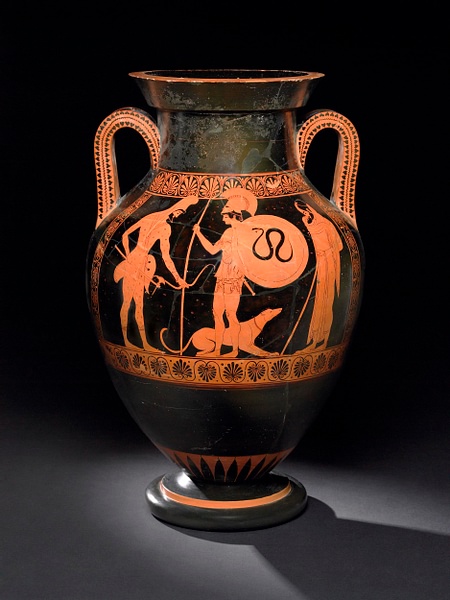

Amphora with Warrior and Dog

The Trustees of the British Museum (CC BY-NC-SA)

Dogs also gave their name to the school of philosophy founded by another of Socrates' students, Antisthenes (l. c. 445-365 BCE), the Cynic School (from the Greek word for dog-like, Kynikos) because their austere lifestyle was similar to that of dogs in that they shunned luxury and made do with what they had or were given. Antisthenes' most famous student was Diogenes of Sinope (l. c. 404-423 BCE), often depicted in later artwork as searching for an honest man in broad daylight with a lantern. Diogenes fully embraced the Cynic view of life by living like a dog on the streets of Athens, owning nothing, and surviving off gifts of food from admirers or those who felt sorry for him.

Dog Breeds & Collars

Dogs were a common sight in the streets of any ancient Greek city but were also highly valued on country estates as guardians and hunters. Xenophon (l. 430 - c. 354 BCE), another student of Socrates, general, mercenary, and author, wrote extensively about dogs c. 360 BCE and, among his wealth of advice, suggests that owners should stick to shorter names of no more than one or two syllables:

They should have short names given them, which will be easy to call out. The following may serve as specimens: Psyche, Pluck, Buckler, Spigot, Lance, Lurcher, Watch, Keeper, Brigade, Fencer, Butcher, Blazer, Prowess, Craftsman, Forester, Counsellor, Spoiler, Hurry, Fury, Growler, Riot, Bloomer, Rome, Blossom, Hebe, Hilary, Jolity, Gazer, Eyebright, Much, Force, Trooper, Bustle, Bubbler, Rockdove, Stubborn, Yelp, Killer, Pele-mele, Strongboy, Sky, Sunbeam, Bodkin, Wistful, Gnome, Tracks, Dash. (Cynegeticus, VII)

Among the most popular breeds in ancient Greece was the Alopekis ("small fox") which is depicted on a ceramic vase dated to c. 3000 BCE. This is also most likely the dog featured on the famous grave stele of a young girl named Melisto of the 4th century BCE (although the dog has also been identified as a Melitan, the modern Maltese). The stele shows the girl, holding a doll in one hand and a bird in the other which she seems to be offering with a gentle smile to the small dog jumping up to greet her.

Grave Stele of a Young Girl, Melisto

Sarah E. Bond (CC BY)

Melisto's grave stele is not unique in representing the deceased with a favorite pet dog, however, as this practice was fairly common. Another grave stele shows a young girl playing with her dog and another depicts a boy playing catch with his. Melisto's stele fairly clearly shows the Alopekis while the others show small dogs whose breed is less certain.

The Alopekis, still popular in Greece today, are small white dogs who were used for vermin control and as companions for women and children. The Melitan was another widely respected breed often chosen as the subject in decorating ceramic drinking vessels (notably the chous type). The most popular dogs for hunting, according to Xenophon, were Laconian hounds (Spartans) of two types: the Castorian and the Vulpine. These dogs, he said, should be of a distinct color, either tan with white markings or black with tan markings, in order to be considered worthy of one's time and effort in training. Leashes were in use at the time of his writing, as he mentions releasing these hounds from them to chase the hare, but what form they took is unknown.

Hunting dogs were important to both the upper and lower class but equally so were farm dogs who protected the flocks and homes from wolves. This threat of wolf attacks led to the development of the uniquely Greek design of collar which had never been seen before: the spiked dog collar. The small Alopekis and the Laconian hounds almost certainly did not wear this collar, but the farm dogs definitely did.

The metal spiked collar served not only to protect guard dogs on the farm but also for wolf-baiting.

It was understood that farm dogs should be white or light in color so that an owner could easily distinguish them from wolves at night. The most popular breed for a guard/farm dog was the Molossian from Epirus. The Molossians, ancestors of the modern Mastiff, St. Bernard, and other large breeds could fend off a wolf easily enough but required protection for their throats. A common collar would have been ineffective against the jaws of a wolf, however, and so the spiked collar was developed.

The Greek collar for the farm dog was made of metal or leather. The metal collars were a kind of chain-link with spikes while the leather ones had the spikes driven through the leather band and secured, by rivets, from the back. It is unclear how actual dog collars were ornamented in ancient Greece but, based upon paintings, grave steles, and drinking cups, one has the impression that they could be small works of art in themselves.

The rhyton - a ceremonial drinking vessel - popularly featured the heads of dogs at their base with the conical cup rising from it. These rhytons (or rhyta) depict the dogs (often hounds) with a brightly colored collar ornamented with images from the owner's life or from mythological works. Other leather collars, depicted in art, are slimmer and most likely used by the lower classes (though not strictly, of course). Metalworking in Greece by this time (c. 2500-2500 BCE), had advanced to the point where iron circlets could be attached to the collar which a leash could fasten on; with the spiked collar, which formerly may have been held by leather strips, metal clasps were used to hold it around the dog's neck.

The metal spiked collar served not only to protect guard dogs on the farm but also for wolf-baiting. Wolf-baiting was both a sport and a legitimate means of hunting to decrease the wolf population. A dog would be fitted with a metal spiked collar and released into an area popular with wolves. When a wolf took the bait, it would go for the throat of the dog, injure itself on the collar, and, thrown off guard, be taken by the waiting hunters. Puppies on farms were trained using leather collars studded with dull metal and then graduated to the sharp metal collars when they came of age.

Conclusion

It may seem, to a modern audience, that these dogs were ill-treated but they were actually well cared for. The Greeks had a deep affection for their dogs and veterinary medicine was well established by the time of Hippocrates (l. c. 460 - c. 379 BCE). The definitive Greek work on veterinary medicine was written by Vegetius (l. late 4th or early 5th century CE) and it is clear people availed themselves of veterinarian services.

Red-figured Jug - Girl Playing with Tortoise

The Trustees of the British Museum (CC BY-NC-SA)

It is equally clear that people played with and enjoyed the company of their dogs as much as dog-lovers do in the present day. Arrian writes that one should encourage one's dog with praise as often as possible:

[You should] pat him with your hand and praise him, kissing his head, and stroking his ears, and speaking to him by name – "Well done, Cirras!" – "Well done, Bonnas!" – "Bravo, my Horme!" – calling each hound by his name; for, like men of generous spirit, they love to be praised; and the dog, if not quite tired out, will come up with joy to caress you. (Cynegeticus, XVIII.1-5)

The ancient Greek advice on training and caring for a dog is familiar, for the most part, to any dog owner in the modern era and, just as people today like to buy their dogs gifts and impressive collars, so did the Greeks. Upper-class collars were made of silver and brass, possibly engraved (as with leather collars) with the dog's name, the owner's name, or both. In this, as in many other ways, the ancient Greeks showed their appreciation and admiration for the dog and, as depicted in Greek art and writing, the dog returned the affection fully.

Did you like this article?

This article has been reviewed for accuracy, reliability and adherence to academic standards prior to publication.

Greek Roman Dogs Line Drawings Kids Easy

Source: https://www.worldhistory.org/article/1604/dogs--their-collars-in-ancient-greece/

0 Response to "Greek Roman Dogs Line Drawings Kids Easy"

Post a Comment